Alfred Wallace

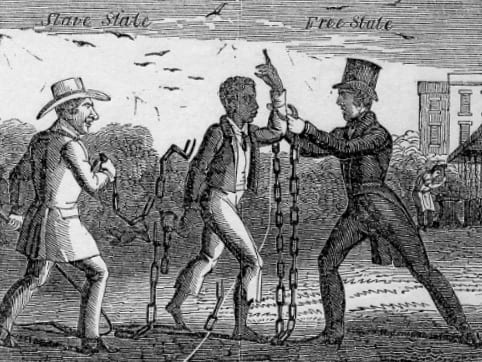

Alfred Wallace, a merchant, registered two bill of sales for “a certain Negro Boy named Nelson about twenty four years of age” at the Washington County court house. In the first one, dated June 15, 1840, Jacob Cartwright conveyed him to Willis Wallace (sometimes spelled Wallis) in exchange for a “boy named Moses and a grey mule,” and in the second, dated one day later, Willis Wallace sold “Nelson” to his brother Alfred for $1000. Hackett later told Canadian authorities that “he was a Slave of Willis Wallace, from the 15th of June, 1840 until December, after which Alfred Wallace told him to come over to his house.”

Wallace Brothers

While little is known about Hackett’s life in Fayetteville, more is known about the lives of Jacob Cartwright and the Wallace brothers, though little of it touches directly on the life of Nelson Hackett or even slaveholding. In the summer of 1840, the very time that ownership of Hackett passed from Cartwright to Willis Wallace to Alfred Wallace, the town was in the final throes of what one participant called the “Fayetteville War.” The Wallace brothers led one faction in the conflict, while minister-turned-lawyer Alfred Arrington and Cherokees associated with the Treaty Party formed the other. Although it certainly built upon longstanding animosity, the Fayetteville War began in June 1839 when Willis Wallace stabbed and killed Nelson Orr, a Cherokee passing through Fayetteville on the Trail of Tears on his way to the Indian Territory. A grand jury, headed by Alfred Wallace and including Cartwright, refused to charge Willis Wallace in Orr’s death. Later that year, after Willis Wallace killed another man on the streets of Fayetteville, Arrington went to the Indian Territory and returned with a force of over thirty armed men determined to bring Willis Wallace to justice. The Wallace brothers assembled a force of their own at their grocery on Fayetteville Square and deployed the town’s cannon to confront Arrington and his allies. Cooler heads ultimately prevailed, and the confrontation ended without more bloodshed, but the town remained tense for several years as low-level violence and fears of Cherokees roiled the population. It remains unknown if Nelson Hackett was among those who took up arms to defend Willis Wallace during the troubles.

It is not clear if Hackett’s sale to the Wallace brothers was related in any way to the Fayetteville War, but the Wallace brothers’ main antagonist, Alfred Arrington, penned the most detailed description of the Wallace brothers: “[Riley Wallace, the youngest] was exceeding cruel without being brave; always ready to fight, but never to fight fairly . . . . Alfred was of a similar character; perhaps he was more intrepid in spirit; but he was less dreaded in that country than either of the others, on account of another strong propensity in his nature, that partially neutralized its excessive destructiveness—he had inordinate acquisitiveness. . . . itchingly avaricious! . . . . [Willis] was wholly a creature of passionate impulses.”

Arrington’s account of the Fayetteville War also provides the only description of any of the Wallace brothers’ interactions with enslaved people. It involves Willis. After murdering a groom at an altar in Georgia, Willis escaped with the help of two enslaved men who were waiting nearby: “with a calm step, he [Willis Wallace] left the room, walked deliberately to the large gate, some hundred paces from the door, mounted his horse, which was there held ready for him, by two of his father’s negroes, who had been waiting his return, with three large double-barrel shot-guns, one of which he took in his hand, cocked both barrels, and they all three rode away at a brisk gallop.” Although Arrington did not witness the episode and exaggerated events to sell books, he understood the Wallace brothers as people who entrusted enslaved men with weapons and depended upon them in a fight.

The Players

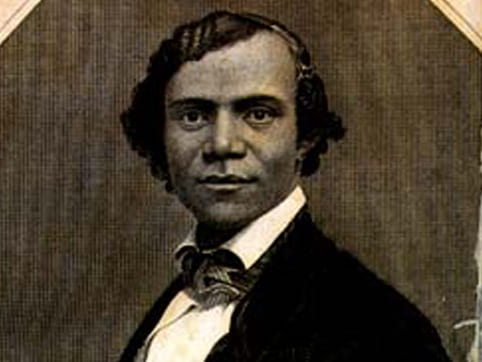

Nelson Hackett

An escaped slave who fled to Canada only to be captured and brought back to Arkansas.

Sir Charles Bagot

Soon after assuming office, Governor General Sir Charles Bagot made the decision to send Nelson Hackett back to Arkansas on charges of theft.

Charles Stewart

Abolitionist and attorney who had been one of the founding officers of the Detroit Anti-Slavery Society and who interviewed Nelson Hackett when he was held in Detroit.

Henry Bibb

Henry Bibb, one of the leaders of Detroit’s Colored Vigilant Committee, helped mobilize support for Nelson Hackett.

Hiram Wilson

Hiram Wilson an abolitionist and an American Reverend ministering to Toronto’s fugitive population who visited Hackett at Sandwich.

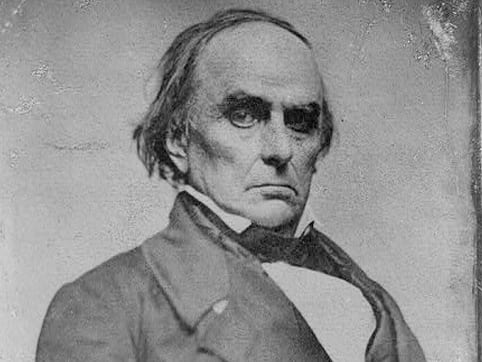

Daniel Webster

As United States secretary of state, Daniel Webster negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842.

Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan led the American abolitionist effort to amend the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Sir Allan Napier MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab presented “Address of the Colored People of Hamilton,” which protested Nelson Hackett’s return to Arkansas, to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

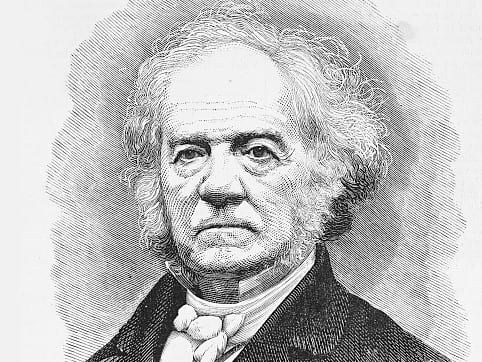

Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson fought to abolish slavery in the British Empire and the international slave trade before turning his attention to Nelson Hackett and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Viscount Palmerston

Viscount Palmerston led the effort in the House of Commons to amend the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to protect fugitives from slavery from extradition.