Nelson Hackett

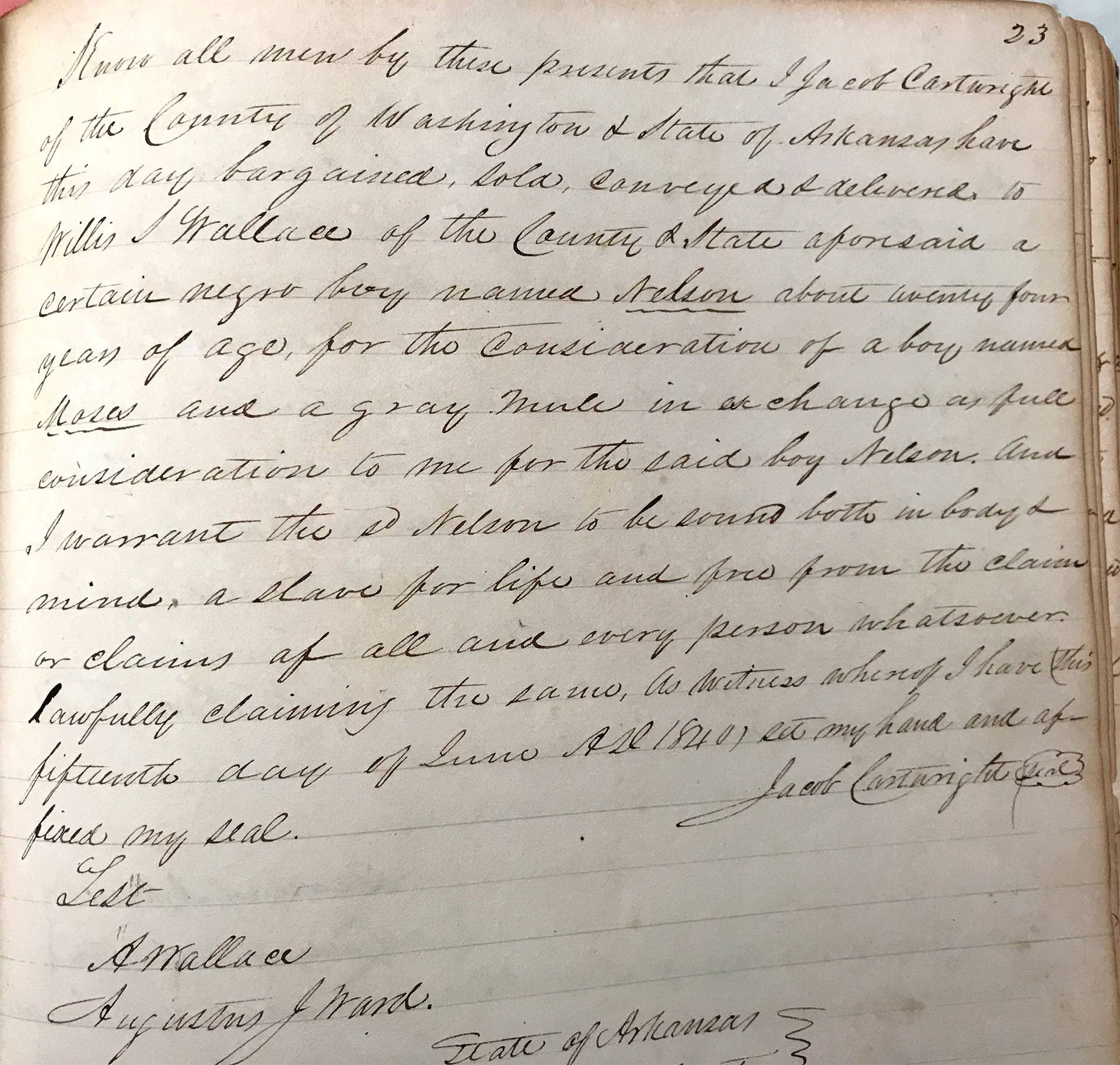

Little is known about Nelson Hackett’s life in Fayetteville. In fact, he does not appear in the historical record until after his escape. At the end of July 1841, Alfred Wallace, a merchant, registered two bill of sales for “a certain Negro Boy named Nelson about twenty four years of age” at the Washington County court house (see image below). In the first one, dated June 15, 1840, Jacob Cartwright conveyed him to Willis Wallace (sometimes spelled Wallis) in exchange for a “boy named Moses and a grey mule,” and in the second, dated one day later, Willis Wallace sold “Nelson” to his brother Alfred for $1000. Hackett later told Canadian authorities that “he was a Slave of Willis Wallace, from the 15th of June, 1840 until December, after which Alfred Wallace told him to come over to his house.” Neither the bills of sale nor the deposition reveal how Hackett arrived in Fayetteville or how Jacob Cartwright came to own him, but they do make clear that Hackett was born around 1817 and that the white people of Fayetteville knew him only as “Nelson.” Why, when, and how he took the last name Hackett, which he used to describe himself in Canada, remains unknown.

There are no known photos of Nelson Hackett. Although the type of hobble used to constrain Nelson Hackett remains unknown, this drawing from 1839 shows the sort of chains often used. Image: Cover of American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1840 (1839).

The little that is known of Hackett’s physical appearance and demeanor comes from accounts of his flight from Fayetteville and legal documents related to his extradition from Canada. A reporter for the Peoria Register and North-Western Gazette, who likely interviewed Hackett on his return to Fayetteville in May 1842, offered the most detailed description of the fugitive and his flight. The journalist described Hackett as “handsomely formed, about 30 years old, of very prepossessing address,” adding that he “wore his hair nicely combed, was genteelly clad, and was in short a negro dandy.” That Hackett signed depositions in Canada with an “X” suggests that he, like most enslaved people, was unable to write.

Bill of sale for Nelson Hackett from the Washington County court house. Jacob Cartwright conveyed him to Willis Wallace and Willis sold him to his brother Alfred.

The Players

Alfred Wallace

The man who claimed to own Nelson Hackett and accused him of stealing a race horse, saddle, coat, 100 £ ($500) in silver and gold coin, and a watch.

Sir Charles Bagot

Soon after assuming office, Governor General Sir Charles Bagot made the decision to send Nelson Hackett back to Arkansas on charges of theft.

Charles Stewart

Abolitionist and attorney who had been one of the founding officers of the Detroit Anti-Slavery Society and who interviewed Nelson Hackett when he was held in Detroit.

Henry Bibb

Henry Bibb, one of the leaders of Detroit’s Colored Vigilant Committee, helped mobilize support for Nelson Hackett.

Hiram Wilson

Hiram Wilson an abolitionist and an American Reverend ministering to Toronto’s fugitive population who visited Hackett at Sandwich.

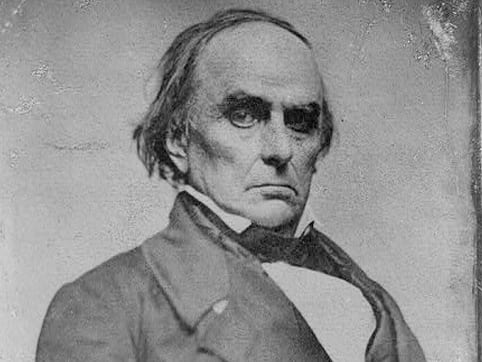

Daniel Webster

As United States secretary of state, Daniel Webster negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842.

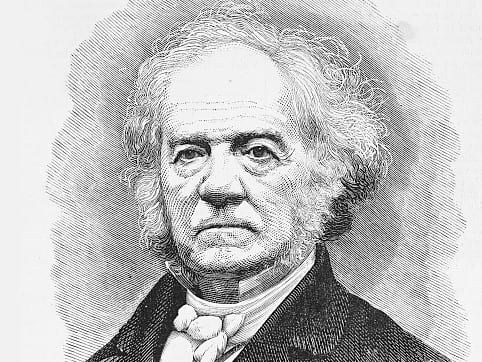

Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan led the American abolitionist effort to amend the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Sir Allan Napier MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab presented “Address of the Colored People of Hamilton,” which protested Nelson Hackett’s return to Arkansas, to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson fought to abolish slavery in the British Empire and the international slave trade before turning his attention to Nelson Hackett and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty.

Viscount Palmerston

Viscount Palmerston led the effort in the House of Commons to amend the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to protect fugitives from slavery from extradition.