Nelson Hackett's Journey

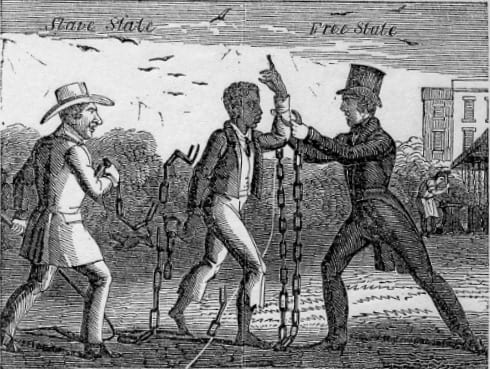

A primary problem in trying to reconstruct Hackett’s flight is that there are few records of his words and thoughts. This problem is rooted in the racism that undergirded chattel slavery and created most of its archival record. Hackett’s flight is therefore reconstructed using other voices, including abolitionists (both white and black), journalists, colonial and elected officials, and slave owners and their apologists.

Scroll down to read the full story or click on any of the following locations:

Fayetteville, AR | Flight Across Missouri | Marion City, MO | Marion City to Chatham | Chatham, Canada | Sandwich, Canada | Detroit, MI | Detroit to Princeton, IL | Princeton, IL | Peoria to Fayetteville, AR | Fayetteville, AR

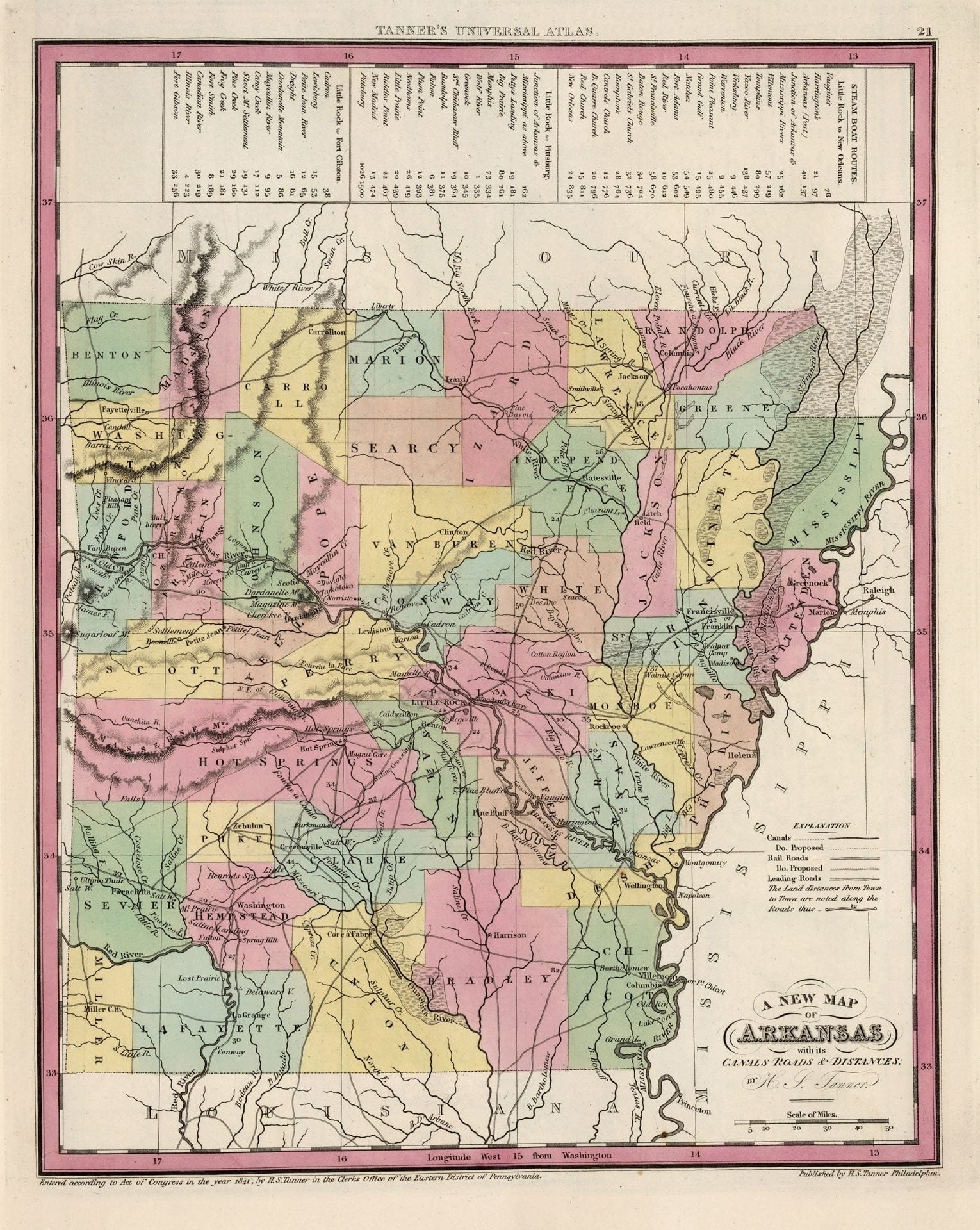

Fayetteville (1841)

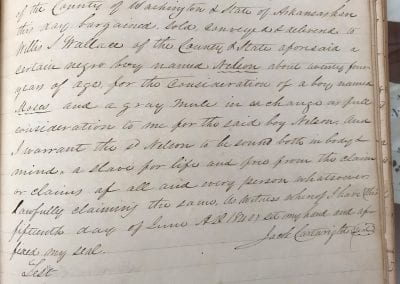

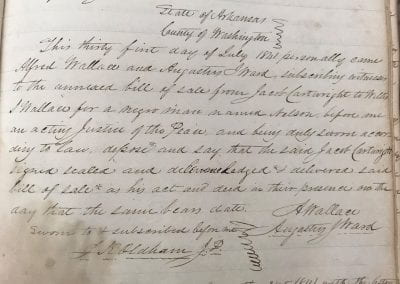

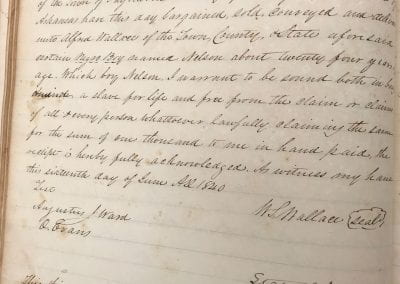

Hackett's Flight BeginsLittle is known about Nelson Hackett’s life in Fayetteville. In fact, he does not appear in the historical record until after his escape. At the end of July 1841, Alfred Wallace, a merchant, registered two bills of sale for “a certain negro boy named Nelson about twenty four years of age” at the Washington County courthouse. In the first one, dated June 15, 1840, Jacob Cartwright conveyed him to Willis Wallace (sometimes spelled Wallis) in exchange for a “boy named Moses and a grey mule,” and in the second, dated one day later, Willis Wallace sold “Nelson” to his brother Alfred for $1000. Hackett later told Canadian authorities that “he was a Slave of Willis Wallace, from the 15th of June, 1840 until December, after which Alfred Wallace told him to come over to his house.”

Neither the bills of sale nor the deposition reveal how Hackett arrived in Fayetteville or how Jacob Cartwright came to own him, but they do make clear that Hackett was born around 1817 and that the white people of Fayetteville knew him only as “Nelson.” Why, when, and how he took the last name Hackett, which he used to describe himself in Canada, remains unknown.

The little that is known of Hackett’s physical appearance and demeanor comes from accounts of his flight from Fayetteville and legal documents related to his extradition from Canada. A reporter for the Peoria Register and North-Western Gazette, who crossed paths with Hackett on his return to Fayetteville in May 1842, offered the most detailed description of the fugitive and his flight. The journalist described Hackett as “handsomely formed, about 30 years old, of very prepossessing address,” adding that he “wore his hair nicely combed, was genteelly clad, and was in short a negro dandy.” That Hackett signed depositions in Canada with an “X” suggests that he, like most enslaved people, was unable to write.

Alfred Wallace and the abolitionists provide differing accounts of Hackett’s escape from Arkansas. Both parties knew that Canada would not return Hackett for simply escaping slavery and tailored their accounts to emphasize or deemphasize Hackett’s alleged thefts. Wallace, who admitted to leaving Hackett unsupervised for “two or three weeks” at a time, testified that on or about July 17, 1841, Hackett stole several items before fleeing Fayetteville. The thefts included a gold watch from the home of a neighbor, Onesimus Evans, and “one roan Mare, aged ___, branded with figure 2 on her left foreshoulder, and also one blue beaver over-coat, the body and collar of which were lined and faced with black silk velvet, and also a quantity of Mexican Silver, and Gold of the coin of the United States, of the value of 100 £” from the Wallace home. Wallace initially claimed that Hackett had raped a white woman before the thefts and escape, but he ultimately dropped the claim, offering no evidence to the Washington County Grand Jury or Canadian authorities that such a crime occurred. Abolitionists, though, portrayed the thefts as incidental to Hackett’s escape. According to Charles H. Stewart, a white abolitionist who interviewed the fugitive in Detroit, Hackett had accompanied Wallace to a horse race “a considerable distance” from Fayetteville. Wallace did not return home but directed Hackett to take the horse and other items back. Instead of heading to Fayetteville, Hackett made his escape. As Stewart wrote, “Hackett finding himself well mounted, under circumstances that permitted absence, directed his course towards liberty . . . . At the time he had in care the outside coat of his master, and he also had his gold watch.” Both accounts are problematic. Wallace admitted to being out of town at the time of Hackett’s escape, not returning to Fayetteville until July 24, but nonetheless he testified under oath about what happened. Stewart never accounts for why Wallace would be travelling with a fur coat in Arkansas in July.

Wallace Brothers

While little is known about Hackett’s life in Fayetteville, more is known about the lives of Jacob Cartwright and the Wallace brothers, though little of it touches directly on the life of Nelson Hackett or even slaveholding. In the summer of 1840, the very time that ownership of Hackett passed from Cartwright to Willis Wallace to Alfred Wallace, the town was in the final throes of what one participant called the “Fayetteville War.” The Wallace brothers led one faction in the conflict, while minister-turned-lawyer Alfred Arrington and Cherokees associated with the Treaty Party formed the other. Although it certainly built upon longstanding animosity, the Fayetteville War began in June 1839 when Willis Wallace stabbed and killed Nelson Orr, a Cherokee passing through Fayetteville on the Trail of Tears on his way to the Indian Territory. A grand jury, headed by Alfred Wallace and including Cartwright, refused to charge Willis Wallace in Orr’s death. Later that year, after Willis Wallace killed another man on the streets of Fayetteville, Arrington went to the Indian Territory and returned with a force of over thirty armed men determined to bring Willis Wallace to justice. The Wallace brothers assembled a force of their own at their grocery on Fayetteville Square and deployed the town’s cannon to confront Arrington and his allies. Cooler heads ultimately prevailed, and the confrontation ended without more bloodshed, but the town remained tense for several years as low-level violence and fears of Cherokees roiled the population. It remains unknown if Nelson Hackett was among those who took up arms to defend Willis Wallace during the troubles.

It is not clear if Hackett’s sale to the Wallace brothers was related in any way to the Fayetteville War, but the Wallace brothers’ main antagonist, Alfred Arrington, penned the most detailed description of the Wallace brothers: “[Riley Wallace, the youngest] was exceeding cruel without being brave; always ready to fight, but never to fight fairly . . . . Alfred was of a similar character; perhaps he was more intrepid in spirit; but he was less dreaded in that country than either of the others, on account of another strong propensity in his nature, that partially neutralized its excessive destructiveness—he had inordinate acquisitiveness. . . . itchingly avaricious! . . . . [Willis] was wholly a creature of passionate impulses.”

Arrington’s account of the Fayetteville War also provides the only description of any of the Wallace brothers’ interactions with enslaved people. It involves Willis. After murdering a groom at an altar in Georgia, Willis escaped with the help of two enslaved men who were waiting nearby: “with a calm step, he [Willis Wallace] left the room, walked deliberately to the large gate, some hundred paces from the door, mounted his horse, which was there held ready for him, by two of his father’s negroes, who had been waiting his return, with three large double-barrel shot-guns, one of which he took in his hand, cocked both barrels, and they all three rode away at a brisk gallop.” Although Arrington did not witness the episode and exaggerated events to sell books, he understood the Wallace brothers as people who entrusted enslaved men with weapons and depended upon them in a fight.

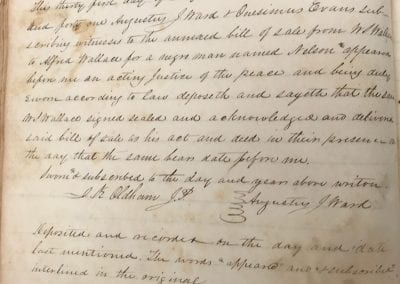

Personal Record Book, Washington County Courthouse, Fayetteville, AR

Bills of sale for “a certain negro boy named Nelson about twenty four years of age” at the Washington County courthouse.

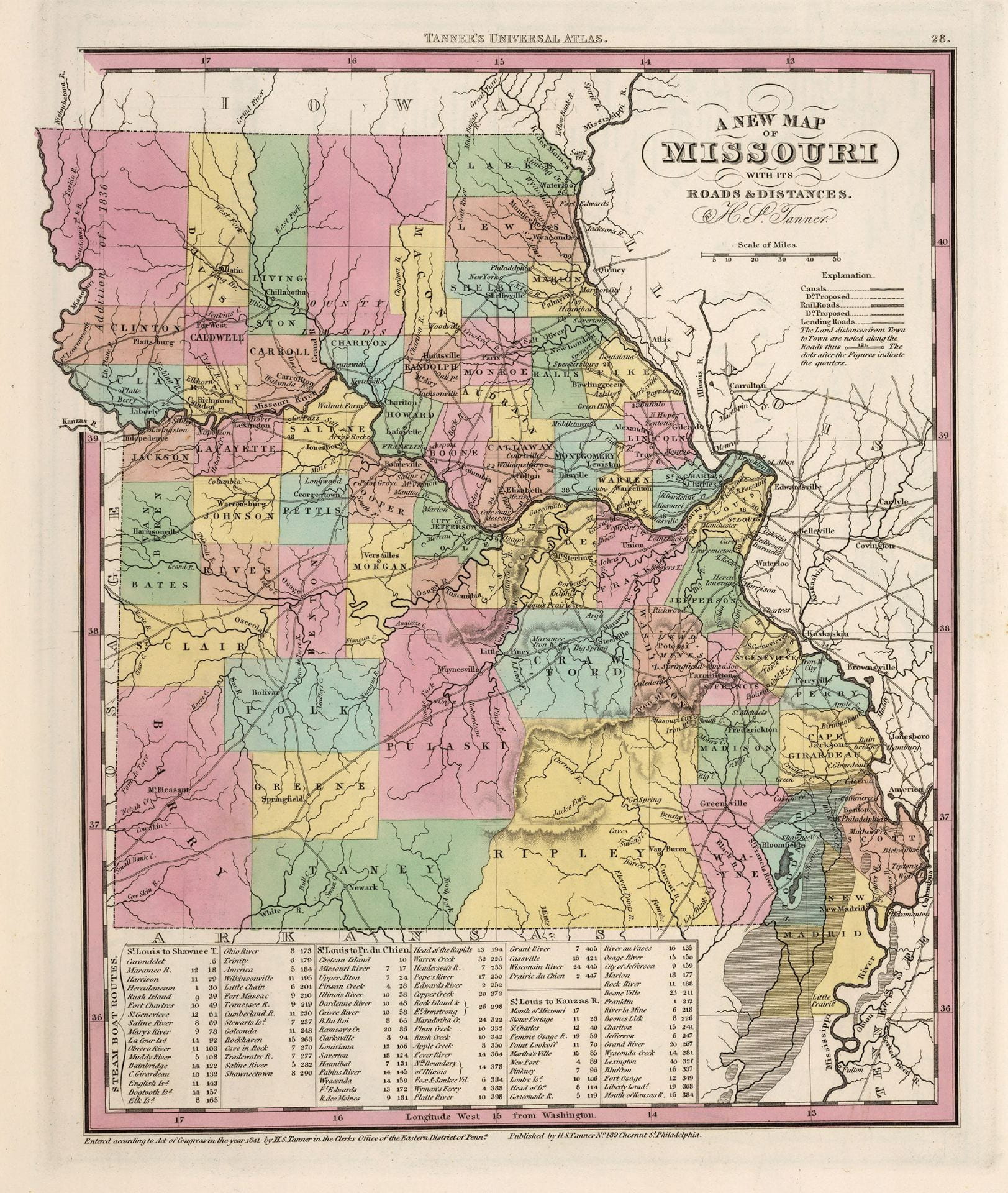

After Hackett fled Arkansas, he headed 360 miles northeast to Marion City, Missouri, on the Mississippi River and not far from Quincy, Illinois. The details of Hackett’s trek across Missouri—his exact route, how he fed himself, who he encountered—remain largely unknown. Aiding or abetting fugitives was considered to be a crime, and Hackett was most likely reluctant to discuss the details for fear of putting those who had helped him in jeopardy. So accounts of the flight, even those written by sympathizers, are not very revealing. The most detailed account, the one by the Peoria journalist, offered: “He travelled only at night, and hiding through the day in the woods, subsisting on such fare as the desert afforded. Upon reaching the Mississippi [should read: Missouri] river, he luckily found the ferry tended by a negro, of whom it is believed he made a confidant, as the same negro subsequently denied all knowledge of the fugitive’s passing that way. The friend thus gained, doubtless furnished him with a supply of food, while by his advice he was probably enabled to proceed more boldly. Avoiding the thoroughfares, he made for Marion city on the Mississippi.” Note that the only other person mentioned—the ferryman—had already been accused of helping Hackett so this account could do him little harm. The ferryman’s fate is unknown.

The Peoria Register’s account suggests that Hackett avoided roads only after crossing the Missouri River. If Hackett had taken the most direct route, he would have travelled northeast on the recently-completed road to Springfield, Missouri, and then due north on another new road through Osage and onto Boonville, where he crossed the Missouri River.

He would have then turned northeast, going overland across a thinly populated section of the state to Marion City. At about 360 miles, Hackett’s journey through areas where slavery was legal ranks it among the longest such overland escapes. Most overland flights were from areas closer to the free states of the North, while longer journeys usually involved ocean or river travel.

Primary Source

“Adventures: Escape of a Slave,” Peoria Register and North-Western Gazette, May 27, 1842. (The article has Hackett crossing the Mississippi River twice [see quotation above]. This is probably a printer’s mistake. The account makes more sense if the first river crossed was the Missouri rather the Mississippi. This mistake tripped up Roman Zorn in his essay on Hackett. Zorn has Hackett crossing the Mississippi River first and then the Ohio at Marion, Kentucky. It is unlikely that Hackett would have taken Zorn’s route. Not only would it have meant an additional 50 miles travelling through slave areas, but also Marion, Kentucky, was not incorporated until three years after Hackett’s escape.)

It is unlikely that Marion City was an accidental destination. Rather the informal information networks among enslaved people had probably told Hackett that the town was a hotbed of abolitionist activity, with blacks and whites ferrying fugitives across the Mississippi River and putting them in contact with the Underground Railroad in Quincy, Illinois. Much of the abolitionist effort at Marion City had originally centered on David Nelson, a white minister. A one-time Tennessee slaveholder, David Nelson emancipated his human property after falling under the spell of Second Great Awakening preachers and moved to Marion County, Missouri, in 1829 to preach at a Presbyterian church in Palmyra. He established Marion College and Marion City on the Mississippi River just east of Palmyra two years later and was run out of the area in 1836 for his abolitionist exhortations. David Nelson moved across the Mississippi to nearby Quincy and continued his agitation, becoming an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society and opening the Mission Institute. Marion City, though, continued to attract, what a local historian called, “a large emigration from Pennsylvania, Ohio and other Eastern and Northern States to the county, and among the emigrants were many Abolitionists.”

Hackett arrived in Marion City at a time when the local conflict between abolitionists and proslavery forces was reaching a fever pitch. Less than two weeks before Hackett passed through the town, three associates of David Nelson—white abolitionists George Thompson, James Burr, and Alanson Work—were arrested near Marion City for abetting fugitives in their escapes. Work’s account of his arrest provides a sense of how fugitives like Hackett would have found help crossing the Mississippi:

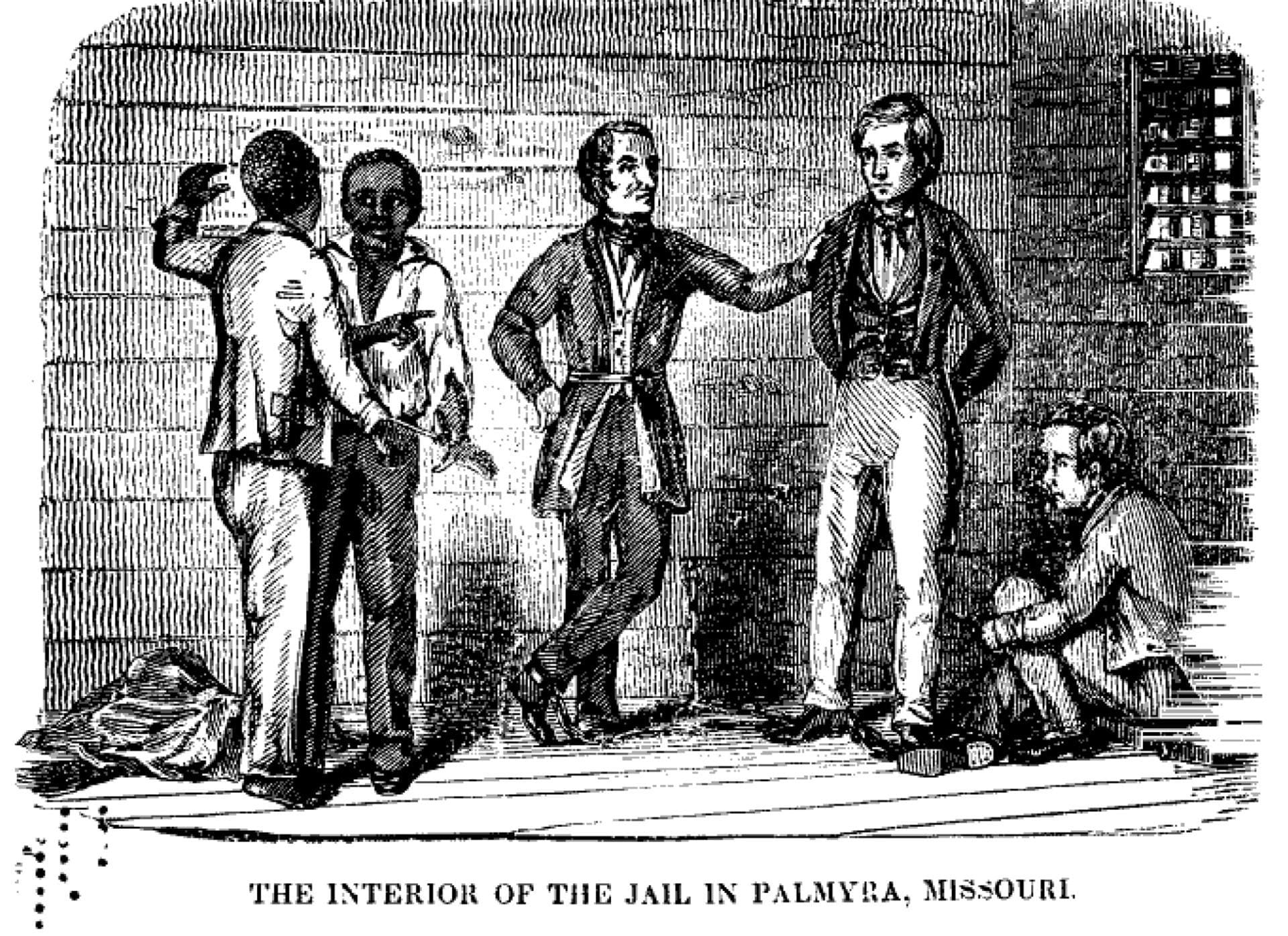

The Palmyra, Missouri, jail held George Thompson, Alanson Work, and James Burr after they were arrested for trying to help fugitives cross the Mississippi River near Marion City shortly before Nelson Hackett made his way through the area. Image: George Thompson, Prison Life and Reflections; or, a Narrative of the Arrest, Trial, Conviction, Imprisonment, Treatment, Observation, Reflections, Deliverance of Work, Burr, and Thompson (1850).

A brother [James Burr] from the [Mission] institute having been in Missouri, saw some slaves who longed for freedom, and agreed to help them across the Mississippi river. On the twelfth of July, in company with him and another brother [George Thompson], I started for the place appointed. James and I walked four or five miles back into the country. The first human being that we saw was a woman and her son hoeing tobacco. James spoke to her, and walked on. He found that she wanted to be free and agreed to help her. We next came to a house. James went in and learned from a slave, the whites being absent, that the slaves he had seen before were in the field alone. We went to them, it being now sunset. We asked them if they were going; they told us they were, and that one living a mile from them, where they had some clothes to get, was going with them, and that they would come three hours after dark. We were seen by white men while with the slaves. After dark we came and waited, anxiously listening for the signal. After some time we heard a distant whistle, and by answering repeatedly soon came to five slaves, three fourths or four fifths of a mile from the river, on a bottom prairie. After salutations and professions, we started in a foot path for the river, rejoicing in the prospect of helping the oppressed to liberty and happiness.

Although none of the extensive documentation of the arrest and imprisonment of Thompson, Burr, and Work explicitly mention Hackett, Work’s jail diary celebrated the escape of many fugitives at the time Hackett would have been in the area. On July 26, 1841, for instance, Work wrote: “we overheard a conversation, by which we learned that six slaves had crossed the Mississippi the night before, and that some persons appeared preparing to go to the river to intercept other fugitives.” It could very well be that Hackett was among the six who had crossed on July 25 or the others trying to do so on the next day.

Just as Hackett knew to flee to Marion City, his pursuers recognized that it was the place he would most likely try to cross the Mississippi. Alfred Wallace had dispatched George Grigg to track Hackett and bring him back to Fayetteville in order “to show his fellow slaves that there was no security for them in Canada.” Grigg, though, could not follow the fugitive’s trail across Missouri, but he picked it up in Marion City. In the words of the Peoria Register, “No trace of him [Hackett] could be found until the officers got to Marion City.”

Primary Sources

Primary Sources Available Online

Narrative of Facts Respecting Alanson Work. Jas. E. Burr & Geo. Thompson, Prisoners in the Missouri Penitentiary, for the Alleged Crime of Negro Stealing (Quincy, IL: Quincy Whig Office, 1842), https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=slavery&handle=hein.slavery/fsrasc0002&id=11&men_tab=srchresults (contains Alanson Work’s account of helping enslaved people escape, pp. 6-7, and his jail diary, pp. 8-13).

David Nelson, “Dr. Nelson’s Lecture on Slavery,” (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, [1839?), https://archive.org/details/ASPC0001969500.

George Thompson, Prison Life and Reflections; or, a Narrative of the Arrest, Trial, Conviction, Imprisonment, Treatment, Observation, Reflections, Deliverance of Work, Burr, and Thompson (Hartford, CT: A. Work, 1850), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;idno=ACK4077.

Secondary Works

R. I. Holcombe Holcombe, History of Marion County Missouri (St. Louis: E. F. Perkins, 1884), esp. 226-248.

Oleta Prinsloo, “‘The Abolitionist Factory’: Northeastern Religion, David Nelson and the Mission Institute in Quincy, Illinois, 1836-1844,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 105 (Spring 2012): 36-68.

Oleta Prinsloo, “The Case of `the Dyed-in-the-Wool Abolitionists’ in Mark Twain Country, Marion County, Missouri: An Examination of a Slaveholding Community’s Response to Radical Abolitionism in the 1830s and 1840s” (dissertation, University of Missouri, 2003).

William A. Richardson, Jr., “Dr. David Nelson and His Times” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 13 (January 1921): 433-463.

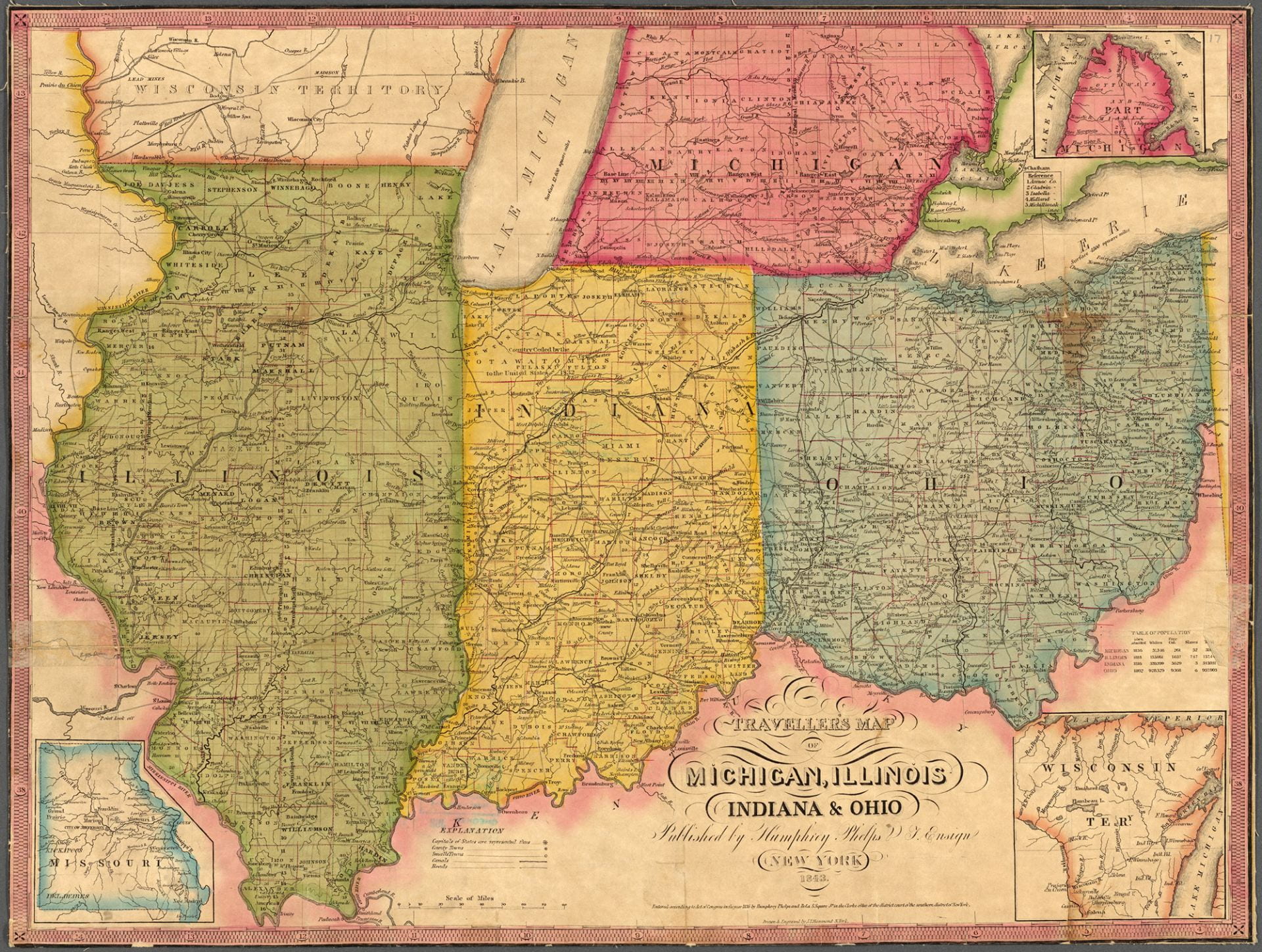

After crossing the Mississippi River at Marion City, Hackett travelled over 600 miles from Illinois to Canada West, arriving there sometime near the end of August1841. Even less is known about this part of Hackett’s journey than his trek across Missouri. The only account that describes it—the one in the Peoria Register—provides only superficial information, the type that seems tailored to avoid putting those who provided assistance in any legal jeopardy. It reads: “Here he [Hackett] breathed freer, and ventured to pursue his journey in the day time. . . . As he journeyed, he would sometimes represent himself as being a free man, living in some county before him, and at others, when he thought it would better answer his purpose, as a slave escaping from bondage.”

The route that Hackett took is similarly obscure. The Peoria Register simply recounted that he moved across Illinois, Ohio, and into Michigan before crossing the Detroit River into Canada. The account’s failure to mention Indiana is probably a mistake; the only likely routes would have gone across parts of that state. Most of enslaved people crossing at Marion City travelled to Chicago or some other spot on Lake Michigan, where they caught a boat for the trip to Canada. Hackett’s route not only took longer but it also exposed him to more people who could have foiled his plans. It is unclear whether he chose this route on purpose or if it was the only one open to him.

Dr. Richard Eells home in Quincy, Illinois, may have been Nelson Hackett’s first stop on the Underground Railroad. Image: Courtesy seequincy.com.

It is probable that Hackett travelled via the Underground Railroad, the network of routes, safe houses, and guides that helped fugitives make their way to freedom in Canada. Quincy, Illinois, just north of Marion City, was a well-known starting point on the Underground Railroad. Just the year after Hackett’s flight, Illinois authorities arrested Quincy abolitionist Richard Eells for helping a Missouri fugitive who swam across the Mississippi River. It is possible that Hackett visited Eells house, just four blocks from the river, before being shepherded to other safe houses on the roads to Canada.

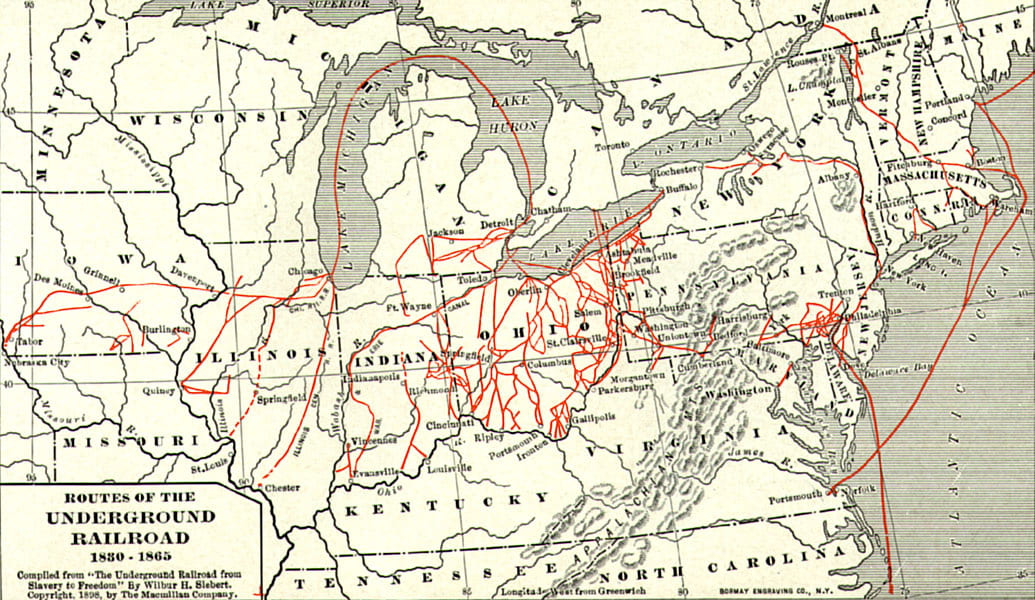

Historian Wilbur Siebert mapped underground railroads routes in his The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1898).

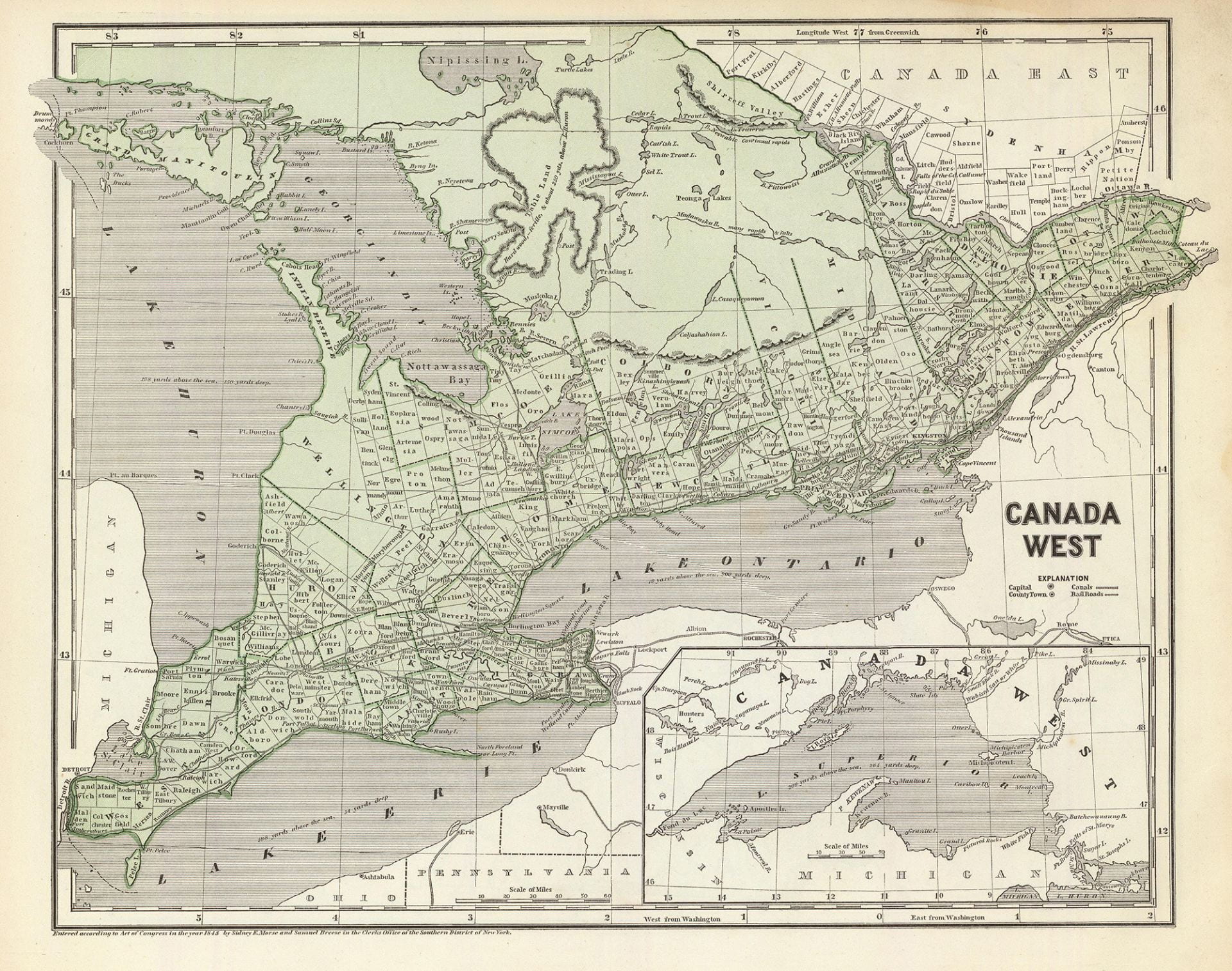

Nelson Hackett made his way to Chatham, Canada West, about 50 miles east of Detroit, in late August or early September 1841. Chatham, when Hackett arrived, was a town of about 600 people, with a reputation as a haven for fugitives. According to one traveler, a good number of formerly enslaved people, who had “run away from their masters in Kentucky,” had set up a vibrant black community in Chatham and the surrounding area. The exact size of the town’s black population in the early 1840s remains unknown (it would be about one-third black by the eve of the U.S. Civil War), but Chatham did have a school for black children and a mission to the black population funded by a British philanthropist. It is not clear if Hackett made Chatham his destination because of its general reputation, by chance, or for some more particular reason.

The increasing number of fugitives arriving in Chatham and the surrounding area produced a backlash, though. White Canadians shared many of the same prejudices and bigotries of their counterparts in the free states of the North. They saw blacks as inferior, dirty, and prone to crime, especially thieving and rape. A black minister traveling through

Chatham in 1843 declared, “The colored people can scarcely walk the streets in many parts of Canada without being assaulted and abused by those having a fairer skin.” It is thus hardly surprising that local authorities treated new arrivals like Hackett with deep suspicion, ready to believe the worst and eager to prevent them from putting down roots.

Hackett’s stay in Chatham was short. On September 6, 1841, Alfred Wallace discovered Hackett’s whereabouts and had a local deputy sheriff arrest him on charges of stealing the horse, saddle, gold watch, beaver coat, and gold and silver coin. Wallace’s case was bolstered when he and the deputy found the horse, saddle, watch, and coat in Hackett’s possession. The next day, while still in Chatham, Hackett appeared before two justices of the peace and allegedly confessed to the theft of all but the coin. The justices ordered Hackett to be held at the district jail in Sandwich, just across the river from Detroit, until he could be returned to Arkansas. Hackett, though, later disputed the confession, stating that the beating he received during his arrest—“over the head with the butt of a whip, and a large stick”—had rendered him incoherent when he had testified. In the later testimony, Hackett also noted that Wallace had initially “charged him with having committed a Rape” in order to arouse the indignation of Chatham’s white community. After leaving Chatham, Wallace never mentioned the alleged rape.

Online Primary Source

William P. Newman, “The Colored People and Canadian Prejudice,” Oberlin Evangelist, January 3, 1844, https://www.gospeltruth.net/oe/oe44/oep004.htm.

Secondary Works

Carmen Poole, “Conspicuous Peripheries: Black Identity, Memory, and Community in Chatham, ON, 1860-1980,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto, 2015), esp. 22-56, https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/71599/3/Poole_Carmen_201511_PhD_thesis.pdf.

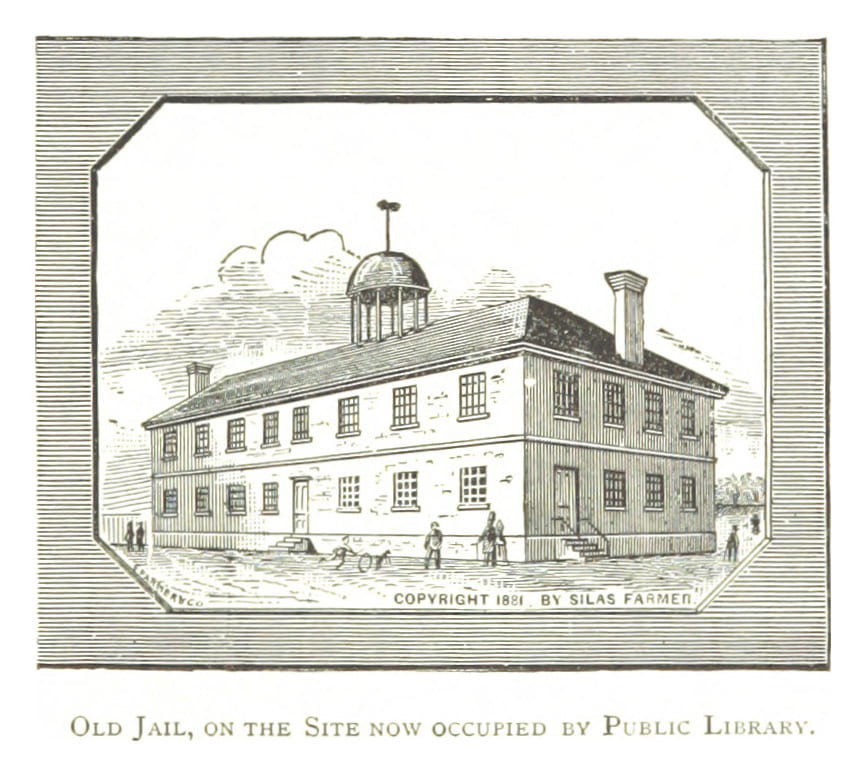

In the middle of September 1841, Canadian authorities transported Hackett from Chatham to the jail in Sandwich (present-day Windsor; across the river from Detroit), and he remained there until the night of February 8, 1842, when he was moved to Detroit in preparation for his eventual return to Arkansas. During the nearly five months that Hackett was in the Sandwich Gaol, authorities in Arkansas, Michigan, and Canada West debated his fate. The fact that there was no formal extradition agreement between the United States and Great Britain concerning Canada complicated the proceedings as did the death of Charles Poulett Thomson, the governor general of the Province of Canada.

Almost as soon as he arrived at the Sandwich Gaol, Hackett, with the help of an attorney identified only as “Mr. Baby,” petitioned to be released. He told Governor General Thomson that he had fled to Canada in the belief that “the humanity of the British law made him a free man as soon as he touched the shores of the country” and asked Thomson to uphold that principle. Hackett explained that the items he was accused to stealing were, in fact, his own belongings and that the severe beating that he received upon apprehension made his purported confession

untrustworthy. The petition concluded that, if Hackett were returned to Arkansas, he would “be tortured in a manner that to hang him at once would be mercy,” a punishment far too harsh for the alleged crime. Hiram Wilson, an American evangelical ministering to the fugitive community in the Toronto area, later insisted that if Thomson had lived long enough to consider the fugitive’s plea that Hackett would have most certainly been emancipated.

On the same day that Hackett petitioned to be released, September 18, 1841, Alfred Wallace began the formal extradition process by convincing the acting governor of Michigan to request that the Province of Canada return Hackett to the United States. The next day, September 19, Governor General Thomson died, creating a situation in which no one had the authority or the willingness to act. The province’s attorney general bought some time by recommending that the acting governor general reject the Michigan application, insisting that any extradition request would need to come from either the United States government or Arkansas’s governor and be based on formal charges made by a grand jury. This prompted Wallace to return to Arkansas to secure the necessary documents. There Wallace got what he needed, indictments of Hackett on charges of “Grand Larceny” from a Washington County grand jury and a formal request for extradition from Arkansas governor Archibald Yell.

The acting governor general then asked the Province of Canada’s Executive Council—a cabinet that advised the governor general—to weigh in on the matter. An Executive Council committee reviewed the petitions and depositions and recommended to the incoming governor general, Charles Bagot, that Hackett be sent back to Arkansas. The Executive Council followed the precedent set in 1829 that a fugitive could only be returned for an offense that would have made him liable to arrest in Canada—being a fugitive from slavery was not a crime in Canada but theft was. The Executive Council concluded that there was sufficient evidence to charge Hackett “had the offence wherewith he is charged been committed in this Province” and that he should be sent back to Arkansas “to be dealt with according to the law.”

Soon after assuming office, Governor General Sir Charles Bagot made the decision to send Nelson Hackett back to Arkansas on charges of theft. Image: Courtesy Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec.

Newly-arrived Governor General Charles Bagot agreed with the Executive Council that Hackett should be returned to Arkansas. Bagot, though, seemed to ignore the earlier precedent and the Executive Council’s reasoning, writing: “There was no doubt of the guilt of this individual, the stolen property having been found on him on his arrival in the province; nor could it be said that this property had been taken solely to assist him in escaping from slavery, and not with a felonious intent. I felt therefore that to refuse to surrender him would be to establish as a principle that no slave escaping to this province should be given up, whatever offence, short perhaps of murder, he might have committed; a principle which would have been repugnant to the common sense of justice of the civilised world, would have involved us in disputes of the most inconvenient nature with the neighbouring states, and would have converted this province into an asylum for the worst characters, provided only they had been slaves before arriving here.” Although Bagot showed more animosity toward Hackett than did the Executive Committee and seemed more interested in domestic tranquility than the moral implications of chattel slavery, he also suggested a higher standard for future extraditions. Whereas the Executive Council thought fugitives should be returned if the alleged crime was a crime in Canada and there was sufficient evidence to file charges, Bagot justified the extradition based on actual guilt, albeit without a trial or a formal investigation. On January 20, 1842, Bagot ordered Hackett to be surrendered to an Arkansas official or authorized agent.

Bagot’s order caught Hackett and those who had been monitoring his situation by surprise. Leaders in the black community in nearby Detroit had visited Sandwich to speak with Hackett and investigate his legal status, and they departed convinced that he would eventually be emancipated. As they later reported, “A portion of our committee made it their business to attend that Court, and there learned from the presiding Judge that Nelson Hackett had been arrested on a charge of felony, and would remain in jail a certified time, and if sufficient proof should be brought within that time, the case would go before the Governor, and as there was no treaty stipulation (then) binding the two governments to agree up fugitives, and as Nelson Hackett was a slave, it was his decided opinion that he would not be given up.” Likewise Hiram Wilson visited Hackett at Sandwich and noted that he was being treated with “unusual leniency” and given the run of the yard. Hackett, according to Wilson, never contemplated an escape, believing that Canadian authorities would release him rather than return him to Arkansas.

Primary Sources

Online Primary Source

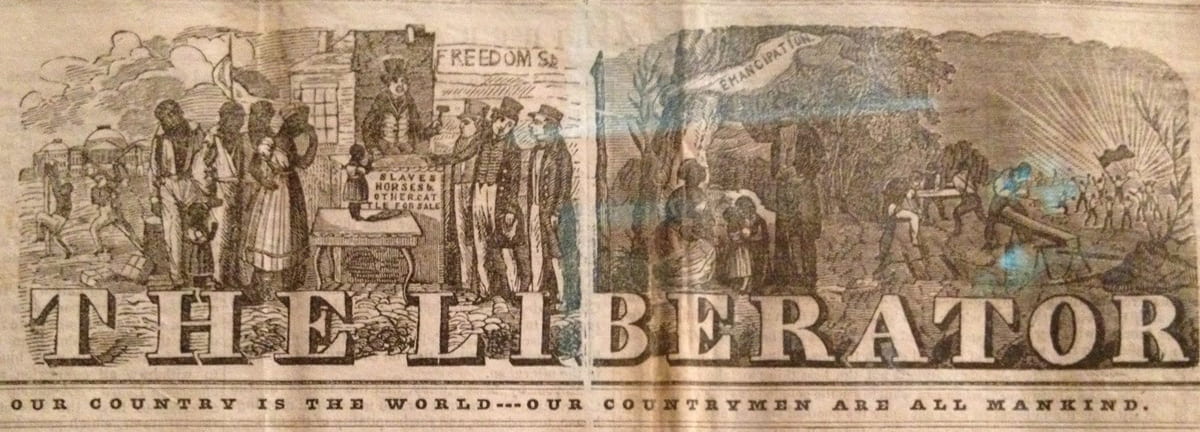

The secretive transfer of a bound and gagged Nelson Hackett from Sandwich to a jail in Detroit on the night of February 8, 1842, prompted that city’s free black population to alert the broader abolitionist community to the extradition. News spread out through resolutions that appeared in abolitionist newspapers throughout the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, making it an international incident. The mobilization of abolitionists, both black and white, came too late to save Hackett, though. Bagot’s decision to send him back to Arkansas and the transfer to Detroit had all but sealed Hackett’s fate.

Lewis Davenport, a Michigan resident who Arkansas’s governor had authorized to take possession of the fugitive, transported Hackett across the river to Detroit in the middle of the night, no doubt trying to keep the transfer secret. Davenport likely feared that blacks on either side of the river would try to free Hackett en route. Just five years earlier at the ferry at Niagara, 100 black men forcibly prevented the return of fugitive Solomon Moseby to the United States, an incident that left two men dead and another wounded. Similarly, members of Detroit’s black community—armed with clubs and pistols—assaulted the county sheriff nine years earlier in a successful effort to secure the release of a fugitive who was about to be taken back to Kentucky.

The fugitive—Thornton Blackburn—found refuge in Canada, but the episode and its aftermath intensified white hostility towards Detroit’s black population and prompted black leaders to counsel a more conservative approach to issues concerning slavery, emancipation, and fugitives.

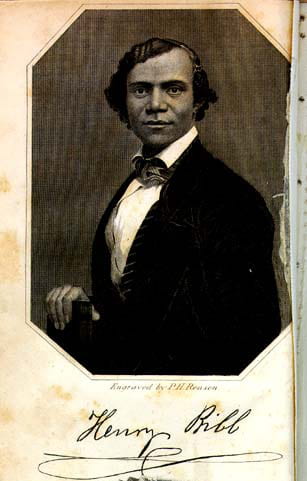

Henry Bibb, one of the leaders of Detroit’s Colored Vigilant Committee, helped mobilize support for Nelson Hackett. Image: Frontispiece of Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself (1849).

On the evening of February 14, 1842—less than a week after Hackett was moved back the United States—the leaders of Detroit’s small free black community of about 200 people (in a city of just under 10,000) met at the Second Baptist Church to consider a response. The leaders, who soon organized themselves as the Colored Vigilant Committee, included William Monroe (sometimes spelled Munro), Robert Banks, and Henry Bibb. The black leaders acted cautiously, worrying that action might cast the black community in a negative light. They asked Charles Henry Stewart, a white attorney who had been one of the founding officers of the Detroit Anti-Slavery Society, to investigate Hackett’s extradition to see if there were any legal avenues that might secure his release. Stewart then obtained a writ from the Michigan Supreme Court that allowed him to speak with Hackett and examine the documents pertaining to Hackett’s case. Stewart and the black leaders concluded, in the words of the Colored Vigilant Committee, that the legal papers had been “correctly made out,” the extradition “had been legally done,” and that Hackett “was a felon.” They worried that associating with such a man would “bring a reproach upon the cause of emancipation” and initially declined to mobilize the community to help Hackett.

The Colored Vigilant Committee reconsidered, though. It later explained:

But the committee feeling themselves duty bound to act in [Hackett’s] behalf called a general meeting of our people and resolved to publish the whole affair to the world.

The general meeting convened on February 22, 1842, and issued a detail resolution criticizing Canada’s surrender of Hackett.

The Colored Vigilant Committee considered Hackett’s extradition as threatening Canada’s status as a haven for fugitives and undermining the British Empire’s commitment to the abolitionist cause. The committee explained that “Hacket was not demanded by the Executive of Arkansas, for the purpose of punishing for larceny, but to punish and make an example of him for the unpardonable offense of absconding from slavery.” If slaveholders could use charges of theft as pretexts for securing the return of fugitives, Canada would become like the free states of the North and “no longer be a safe asylum for our unfortunate brethren who are fleeing from bondage.” The Colored Vigilant Committee ordered that copies of the resolution be sent to abolitionist papers in an effort to make Hackett’s case known to the world.

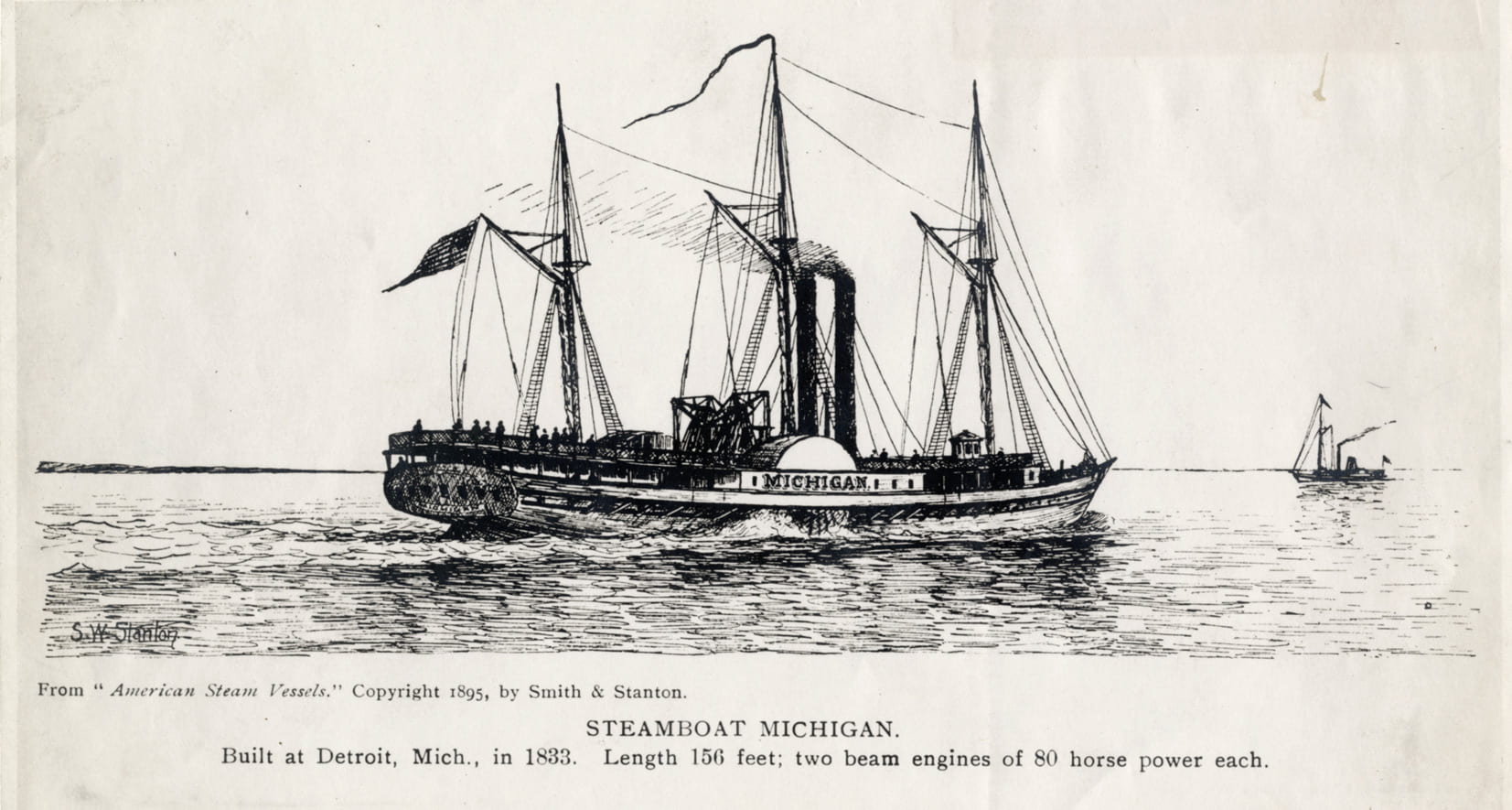

Hackett remained in the Detroit jail until spring, waiting to be taken back to Arkansas. Davenport planned to travel mostly over water—Great Lakes ship to Chicago, stage to Peoria, steamboat down the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, and then onward to Fayetteville. Such a journey had to wait until late spring when the ice cleared on the northern Great Lakes. Hackett, Davenport, and Onesimus Evans, who had recently arrived from Fayetteville to help transport the prisoner, departed on a Great Lakes steamship around May 1, 1842.

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Roy Finkenbine, “A Community Militant and Organized: The Colored Vigilant Committee of Detroit,” in A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland, ed. Karolyn Smardz Frost and Veta Smith Tucker (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2016), 154-164.

David M. Katzman, Before the Ghetto: Black Detroit in the Nineteenth Century (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973), 38-50.

Bryan Prince, “The Illusion of Safety: Attempts to Extradite Fugitive Slaves from Canada,” in Frost and Tucker, A Fluid Frontier, 67-79.

As they were leaving Detroit in May, Hackett’s captors, Lewis Davenport and Onesimus Evans, fitted him with a hobble—iron chains that restricted the movement of his hands and feet. The three men heading to Arkansas quickly fell in with four men from western New York who were making their way to Iowa to investigate land purchases. The New Yorkers befriended Hackett’s captors and began to take turns watching the fugitive. The trip took them north across Lake Huron and south the length of Lake Michigan to Chicago, a total of about 600 miles. There is no indication as to why Davenport and Evans chose to travel by boat rather than road, but the water route was quicker, less physically demanding, and afforded fewer opportunities for escape, especially for someone in irons.

A steamship like the Michigan would have transported Nelson Hackett and his captors from Detroit to Chicago. Image: Samuel Ward Stanton, American Steam Vessels (1895). Courtesy Detroit Public Library Digital Collections.

Arriving in Chicago on May 8 or 9, 1842, Hackett, his captors, and the four New Yorkers—boarded Winters’ Stagecoach for the four day/three night trip to Peoria, a distance of about 150 miles. Evans and Davenport continued to force Hackett to wear the hobble, no doubt to prevent escape. The trip was uneventful until the third night—probably May 12—when the stage stopped in the town of Princeton, about 55 miles north of Peoria.

In Princeton on the night of May 12, 1842, or thereabouts, Nelson Hackett escaped and remained at large for two nights before he was recaptured. Like Marion City and Quincy, Princeton was a center of Underground Railroad activity, much of it revolving around the white abolitionist Owen Lovejoy who had moved to the town in 1838. Lovejoy, while serving in Congress in the late 1850s, boasted of his longstanding efforts to assist those fleeing slavery on their way through Princeton: “Owen Lovejoy…aids every fugitive that comes to his door and asks it. Proclaim it then from the housetops. Write it on every leaf that trembles in the forest, make it blaze from the sun at high noon…I bid you defiance in the name of my God!” Hackett’s captors, perhaps aware of the town’s reputation, isolated him from the townspeople. The account in the Peoria Register noted, “Care was taken to keep Nelson as secluded from observation as possible, and he had no converse with a single person in Princeton.”

It is not clear if Hackett knew of Princeton’s reputation, sensed his captors’ anxiety, or just felt that the town just afforded him the last best chance of freedom, but that night he escaped. Before the seven men went to sleep in a second story room of a tavern, Hackett’s captors made sure that the windows and doors were secured, but one of the men woke at about 3:00 am to discover that Hackett had freed himself from his hobble and fled through a window. The Peoria Register explained, “The jump from the window was by no means perilous, it being but 10 to 12 feet to the ground, but everything else connected with his escape is a mystery.” The paper speculated that Hackett might have somehow been aided by one of the New York travelers but admitted that there was no evidence that that had happened.

Hackett’s captors and the New Yorkers began searching for the fugitive that night, but had no luck. The next day, the New Yorkers continued their journey, and Davenport and Evans remained in town to announce rewards for Hackett’s capture: $200 if delivered to St. Louis or $100 if delivered to Detroit. Hackett never connected to the Underground Railroad, and the reward did the trick. After wandering for two days and two nights, Hackett approached a farm just seven miles from Princeton to ask for some food. The farmer, though, seized the fugitive, delivered him to Lewis Davenport and Onesimus Evans who were then in Peoria, and claimed the reward.

After the farmer delivered the fugitive to his captors in Peoria and fetched the reward, Nelson Hackett, Onesimus Evans, Lewis Davenport continued their trip to Fayetteville. The three boarded the steamer Mermaid for the journey down the Illinois River to the Mississippi and arrived in St. Louis on May 26, 1842, at which time Hackett was put up in the city jail to prevent another escape. It is unclear how Hackett and his captors travelled from St. Louis to Fayetteville. An overland trip via Springfield, Missouri, would have been about 340 miles. More likely, though, they took a steamboat down the Mississippi to Napoleon at the mouth of the Arkansas River and then another steamer up the Arkansas to Van Buren. The overland portion would then cover 50 miles.

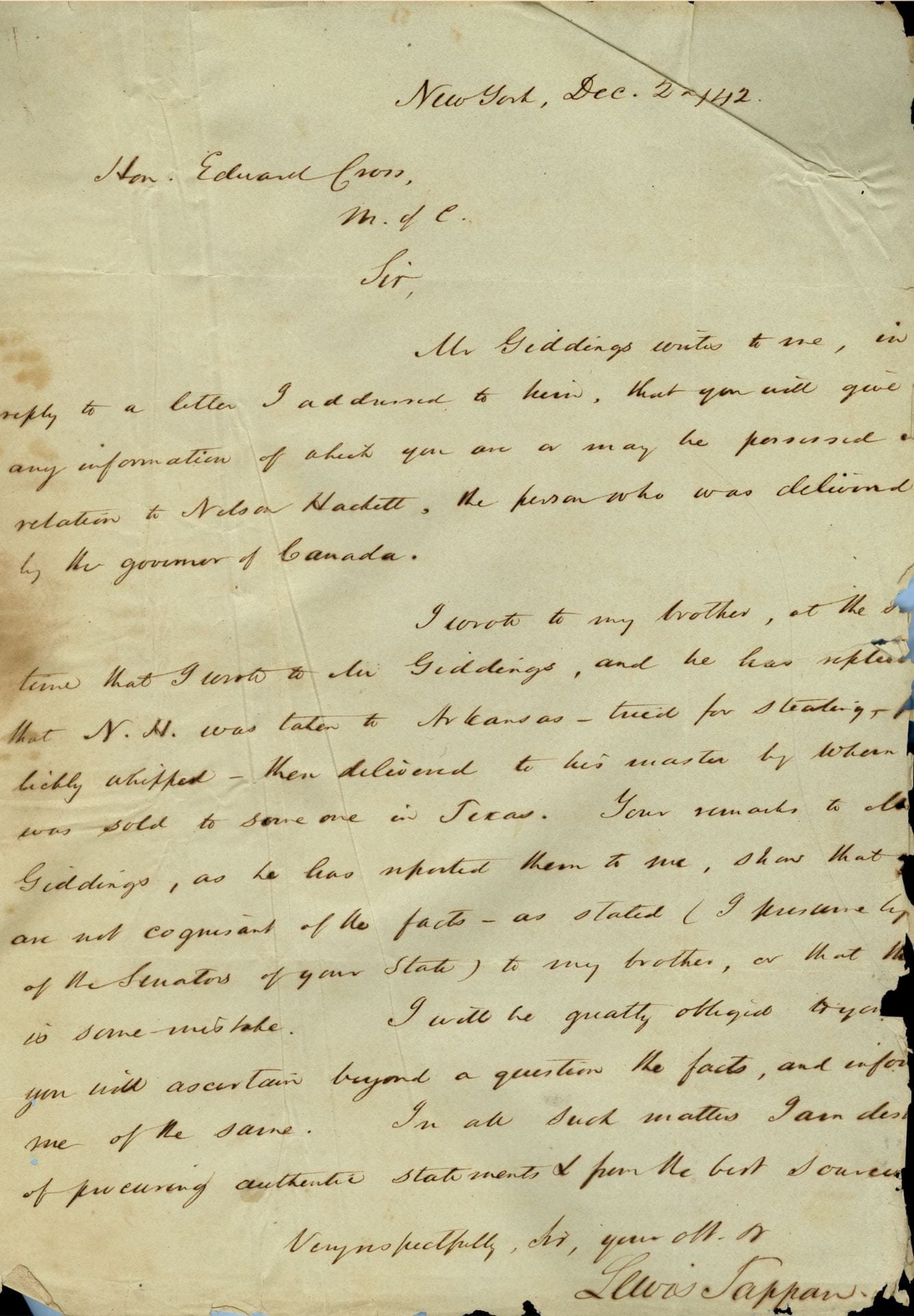

The most detailed account of Nelson Hackett’s June 1842 return to Fayetteville appeared nine years later in the June 6, 1851 edition of the Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s fiery abolitionist newspaper. It came from William Murdock, another enslaved man from Fayetteville who was owned by Alfred Wallace, after he escaped and made his way to Canada in the early 1850s. There Murdock recounted to abolitionist Hiram Wilson what happened to Hackett: “William informs me that Nelson Hackett was brought back by [Alfred] Wallace, his master, who had four hundred and fifty slaves on his plantation—that he was kept in handcuffs and fetters for some time, and closely watched besides—that he was flogged with great severity five or six times, and then sold off to the interior of Texas—that the first whipping, which was done in the presence of all the slaves, consisted of 150 lashes upon his naked body. His whippings afterward varied from 39 to 50 to 60.” Wallace certainly did not hold 450 people in bondage, but Wilson most likely confused the number of enslaved people owned by Wallace with the entire population of the Fayetteville community. The rest of the account, though, is consistent with information that an Arkansas official—probably one of the state’s U.S. senators—supplied to abolitionists Arthur and Lewis Tappan in late 1842: “N. H. was taken to Arkansas—tried for stealing & publickly whipped—then delivered to his master by whom was sold to some one in Texas.”

The sale of Nelson Hackett to traders could not have netted Alfred Wallace anywhere close to the amount expended in securing the extradition. The new lashes on Hackett’s back marked him as especially difficult and, undoubtedly, drove down his value well below the $1000 that Wallace had paid his brother less than two years earlier. Wallace’s expenses were enormous, though. He had paid George Grigg to trail him, travelled to Chatham himself, secured the services of a Sandwich attorney, hired Lewis Davenport to bring Hackett back, sent Onesimus Evans to help with the return, gave a $200 reward to the farmer in Princeton, and footed the bill for everyone’s transportation, food, and lodging. Davenport estimated that Wallace had already spent close to $1500 at the time Hackett was transferred to Detroit. Accounts suggest that Wallace desired Hackett’s return as a lesson to other slaves rather than for economic reasons. According to Davenport, “the principle inducement to getting Hackett back was to deter other slaves from running away.” But still the costs must have driven the “itchingly avaricious” Wallace crazy, especially in light of abolitionist offers to buy Hackett before his return to Arkansas.

While still in Fayetteville or on his way to Texas, Hackett escaped yet again. This is known because Arkansas’s representative in Congress—Edward Cross—visited abolitionist Joshua Leavitt, an associate of Lewis Tappan, in Washington, DC, to tell him. Leavitt recounted the conversation in a letter that appeared in the London-based British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter. After his return to Fayetteville, Hackett “escaped a third time, and has not been heard from since; and whether he has gone clear, or is destroyed, is not known.” Hackett’s fate will remain unknown unless additional evidence is located.